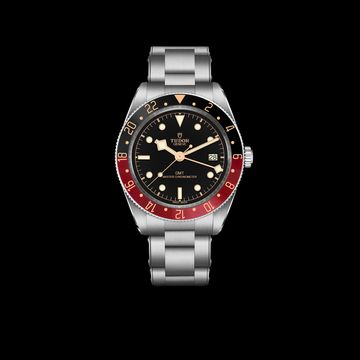

In March last year Nomos Glashütte’s new Metro watch was more than a breezy, colourful new design from the young German manufacture; it represented an important technical breakthrough too. As many readers will know, Nomos started up in the watchmaking town of Glashütte soon after the Berlin Wall came down, making watches in the Deutsche Werkbund tradition of “form follows function”. After some years designing, ordering components and assembling them, Nomos invested in the capacity to actually manufacture its own movements, which it has been producing since 2005.

With the Metro, it announced that this also now included making the watch escapement assembly; what Nomos is describing, with its usual joie de vivre, as its “Swing System”. To understand what is so special about it, we need a little bit of history.

Prior to the Quartz Crisis of the 1970s, most watch firms were watch assemblers rather than makers: they bought cases, movements, dials and hands from specialist suppliers and put them together. This was the most efficient way to produce a mass-market commodity. Through the 1990s, when the mechanical watch was reinvented as a luxury product, this system started to become unstable. ETA, the major European watch movement manufacturer, or more specifically its legendary proprietor, Nicolas G Hayek, became restive; why should he be investing heavily to satisfy the escalating demands of other marques, when the expanding requirements of his own (Swatch Group) brands were difficult to meet? Swiss competition authorities however ruled that restriction of supply to others would be an abuse of a monopoly position and effectively ordered a stay of execution.

Degrees of in-house

Over the last few years alternative movement suppliers have begun to emerge, as well as a growing number of brands claiming to produce their own movement “in-house”. The claim is generally a bit of a fudge, however, as hardly any can produce the escapement assembly – what the Swiss call the “assortiment” and Nomos its “Swing System”. The escapement assemblies for most movements are still supplied by Nivarox, another Swatch Group company and another Sword of Damocles hanging over the heads of other watch brands.

Making watch movements then, apart from the escapement assembly, is arguably really a matter of buying some rather expensive computer-controlled machines and hiring some machine minders. In fact this is no small matter in itself, and the ability to design and execute new movements in volume still requires years of investment, development and expertise. But producing the escapement assembly itself – and removing reliance on Nivarox or an equivalent supplier from the equation – is quite another step, and the reason Nomos is so proud of its Swing System. Why this is requires a bit more information.

Why an escapement is such a tricky thing

In spite of what the companies would have us believe, watches are rather crude mechanisms. They were after all made using simple hand tools in the Middle Ages. Admittedly they did not keep time very well. The difficult bit was, and is, the escapement. This, together with the oscillator, determines the accuracy of the timekeeping and, as it is the limiting factor in performance, has always required working at the leading edge of contemporary technology. The levels of precision required to produce and adjust the escape wheel, pallets, lever, balance and balance spring are quite another matter. They require highly specialised equipment and very skilled technicians.

In describing its Swing System Nomos likes to use the analogy of the football team; to achieve success the components must not only fit their individual roles but also work well together. The escape wheel teeth must be perfectly concentric. Perfection is not of course possible but they must be much closer to perfection than any other wheel in the train.

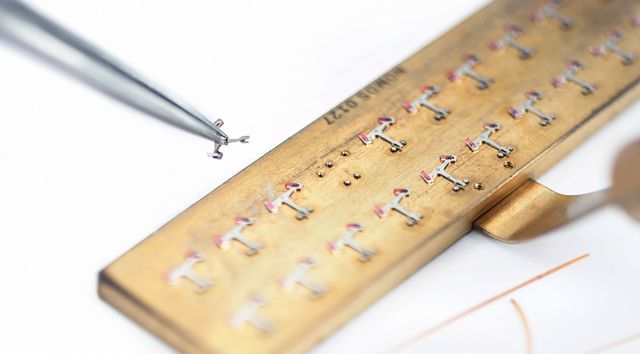

Currently Nomos produces the majority of the components of the escapement assembly but some are produced by an outside supplier, to Nomos specifications, and fitted by Nomos watchmakers. The escape wheel has to be fitted to its pinion and shown to run true. The guard pin is riveted to the lever and the pallets fitted. The latter is done with shellac, the traditional heat-sensitive adhesive which allows them to be positioned precisely when placed on a warm block under a microscope. The balance wheel is fitted to the balance staff, as is the impulse roller with its impulse jewel.

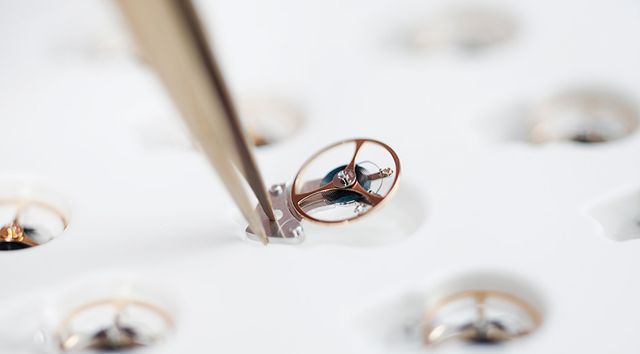

A specialised machine, a Balance-o-Matic, is used to check the balance assembly; perhaps unsurprisingly, it must “balance”. This is the watchmaking equivalent of wheel-balancing in a motor car; but instead of adding small weights to the wheel rim, a small radial mill is used to reduce the weight of heavy sides of the wheel.

Although the balance wheels are now balanced, the limits of manufacturing tolerances mean that they will not all be the same weight, or have exactly the same dimensions; their moments of inertia will therefore differ. In the same way, but perhaps for different reasons, the torque of the balance springs will vary. This problem is dealt with by another highly specialised machine, the Class-o-Matic. It enables the operation of what we might call the “Goldilocks Principle”. The balances are sorted into several different classes according to their moment of inertia; likewise the balance springs according to their torque. They can each then be paired with a partner that compliments their properties most accurately.

Planting the escapement

The escapement components must not only approach levels of individual perfection, they must be assembled correctly so as to bear the correct relationship with each other. This is called “planting the escapement” – adding it to the movement. This in itself is one of the most difficult operations in all watchmaking, and another skill that the Nomos team has had to perfect, unlike most other brands.

With one exception, making watch components is all a matter of dimensions. You could almost reduce it to a matter of surfaces; provided the surfaces in contact have the right shape, position and surface properties, the watch will run. The exception is the traditional balance spring. Early balance springs were made of steel, gold, or even glass, but they all suffered from the fact that their elasticity varied with temperature, limiting the accuracy of the watch (bimetallic balances were made to try to correct this, but that’s another, and not entirely successful, story).

The temperature problem was solved by a Swiss Physicist, Charles Édouard Guillaume. He invented an iron/nickel alloy, which had a very low coefficient of expansion, which he called Invar and for which he received a Nobel Prize in 1920. He also developed a similar alloy, Elinvar, whose elasticity showed little change with temperature and was ideal for balance springs (I said he was Swiss). This alloy also included small amounts of other metals and a number of variants have been developed subsequently. By far the most widely used is Nivarox, produced by the eponymous Swatch Group subsidiary that supplies most European watch escapements.

These iron/nickel alloys behave in most peculiar ways. It’s not just a matter of getting the composition right. As the mixture cools it becomes very heterogeneous; the component metal atoms tend to sort themselves out and form clusters of varying sizes and properties depending on the rate of cooling and the way the subsequent metal is handled. When the ingot is cut into strips, drawn step by step into ever finer wire and then rolled into a ribbon, cut into lengths to form spirals and heat-treated to form springs, successive springs are found to have different properties. Swatch Group refuses to comment on the reason for this. Nomos now obtains its springs from a German supplier (it won’t say who), and states that in perfecting the Swing System there has been extensive collaboration with the University of Dresden – but mostly in mathematics.

The financial mathematics are worth noting too. Most Nomos watches retail from £1,000 to £3,000. The company has invested almost £9 million on the Swing System but claims that watch prices will not be affected. Expecting this investment to be recouped by growth, in the current climate, shows quite extraordinary self-confidence. But given the brand’s steady progress over the years and its loyal – almost cult – following it would be hard to say this is misplaced.