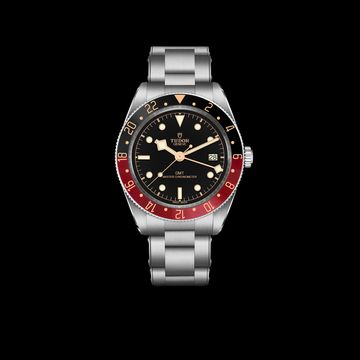

In a watch industry obsessed with ever-more exotic metals, it’s no wonder that meteorites are increasingly big news - the metal has often travelled billions of miles, and could come from the dawn of our solar system. Why would you wear anything less?

Brands such as Bovet, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Parmigiani, Romain Jerome and Zenith have all used meteorite - and Omega, makers of the first watch to travel into space, now make a Speedmaster with slices of a meteorite which fell on Namibia.

But the history of meteorite watches and jewellery is longer - and stranger - than you imagine, according to David Bryant, Britain’s only professional meteorite dealer. The market is also changing fast.

Meteorites are increasingly sought after - not only by watchmakers, but by the makers of halal knives ("There’s a lot of demand for meteorite for use in halal knives - when it’s laminated, it looks incredible. It’s incredibly fine and untarnished", Bryant tells us), and collectors in America and Germany. Other meteorites - some older than our planet, and unchanged after billions of years in the void - are sought by scientists for traces of the early history of the solar system.

‘Three hundred tonnes of meteorite arrives on Earth every day,’ says Bryant. "But the majority of it is dust, and a lot arrives in fairly remote places and in oceans. Very few are seen arriving. Meteorites stick out when they arrive in desert regions, so quite a lot are found there. In the Sahara, it’s mostly limestone, so it’s white. When meteorites arrive, they have a charred outer surface - a fusion crust - which is black, so it’s clearly visible."

So where did the one on your wrist come from? Many watchmakers have used metal from the Gibeon meteorite which fell in Namibia in prehistoric times, which was found in 1836 and named after the nearest town.

The iron meteoritic material, rich in cobalt and phosphorous, found in the 62-mile wide ‘strewn field’ in Namibia is prized for the beautiful patterns found when thin slices of it are acid-etched. Rolex used Gibeon material for its Daytona meteorite model - as did Omega for its Speedmaster Grey Side of the Moon. Namibia has now banned further harvesting of Gibeon meteoritic material, but it’s still widely on sale.

‘The ‘Widmanstätten’ pattern found in octahedrite iron meteorites, when you cut a thin slice is very, very beautiful - and completely extraterrestrial,’ says Bryant. These are the patterns we're most familiar with on watch dials, and arise from long nickel-iron crystals. Specifically, two varieties of nickel iron crystal (kamacite and taenite) are interwoven.

The gaps between crystals fill with a fine-grained mixture of the two, called plessite. The patterns take their name from the impeccably titled Count Alois von Beckh Widmanstätten, director of the Imperial Porcelain works in Vienna in 1808, who first noticed the pattern formation while heating meteorite metal.

It’s not the easiest material to work with. The material is magnetic, so it has to be rhodium-plated for use in watches, but the pattern is unique, forming in the meteorites as they cool, and revealed when the material is sliced and acid-etched. The angle of the pattern on the dial depends on which plane the raw meteorite has been cut. Compare the Cartier, above, with the Romain Jerome below, for instance.

"Watchmakers using meteoritic material is not a new thing,’ Bryant says, ‘It’s always been part of that quest for rarer and rarer materials. I know of meteorite material being used in a watch bezel in the Fifties".

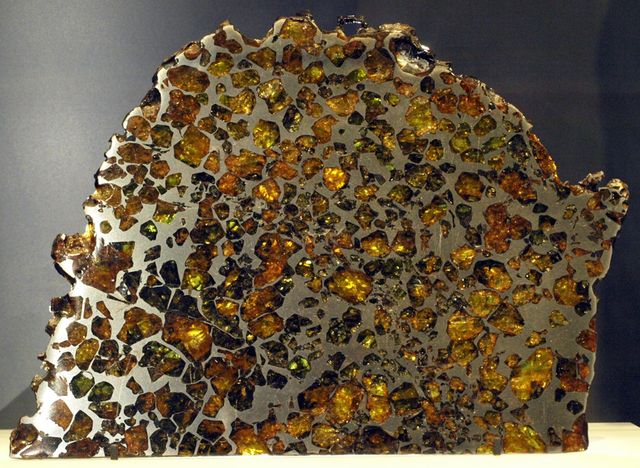

Other meteoritic materials can be even more beautiful - and are already widely used in jewellery, Bryant says.

Bryant says, "In pallasites, you can see [olivine] crystals suspended in a nickel iron matrix, and it’s very beautiful. It’s also very, very rare - impossibly so, far rarer than gold."

But the market for space rocks is changing rapidly, Bryant says, with many countries clamping down on the import and export of meteorites. Bryant describes federal police and customs agents patrolling a recent meteorite fair in Argentina, looking for illegally-exported rocks.

Morocco remains one of the few countries which does not control the import and export of meteorite - and so many meteorites come via markets near the Moroccan city of Rissani. "A few are seen arriving in the desert, then they’re found by local people," says Bryant.

"They’re often brought there by Berbers and Tuaregs on camels and donkeys (and in Toyota Landcruisers). Moroccan dealers buy them, but it’s not always clear where they have come from."

But while the provenance of some space rocks might be dubious, the material used in watches tends to come from well-known meteorites - such as the Campo de Cielo rock from Argentina, which fell about 4,000 years ago, and the Gibeon meteorite. Bryant says that the trend is unlikely to die out any time soon.

"It’s getting ridiculous," he says. "I think it’s a generational thing - we’re obsessed with space travel. We know more about the chemistry of Mars from meteorites than we do from six spacecraft visiting it. They have a very high extrinsic value."

"Meteorites were found in objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb, and in statues of Buddha. It’s the same as the watches worn by the Apollo moon walkers - they’re the ultimate present, something that is not from this world."