Were you to ask even the average watch enthusiast which companies produce the most mechanical movements in Switzerland today it’s unlikely many would think to include Sellita. This is perhaps understandable given that the Chaux-de-Fonds manufacturer is in the business of keeping its customers – namely watch brands – happy rather than marketing its services to the end consumer, millions of whom unknowingly wear watches containing one of its movements.

Sellita has always been a B2B enterprise, quietly supplying the watch industry with a huge number of tried-and-tested mechanical movements each year. In recent years that number has been as high 1.2 million annually; to put it into perspective, that’s more movements than Rolex and is only exceeded by the output of the Swatch Group/ETA.

But Sellita’s reliance on watch brands buying its movement has seen it suffer more than most in the recent industry downturn, with business down 50 per cent over the last three years. Now, with sales starting to recover, the privately owned firm is about the embark on the latest in a series of changes it has had to make to adapt to seismic shifts in the watch industry.

Sellita has only been selling its own movements for the last 14 of its 68 years in business and the movements it has supplied since 2004 have almost all been based on historic, out of patent ETA designs. Now Sellita plans to move forward with a new wave of original, high performance movements to differentiate itself from the competition.

Work has already begun on a 5,000sq m extension on a neighbouring plot of land purchased from the Swiss post office. When finished, the state-of-the-art production facility will allow Sellita to increase production and be linked to the existing factory, itself only five years old, by a glass walkway.

The company has also brought in a host of new talent to develop these new movements such as lawyer-turned-watchmaker Dr Sebastien Chaulmontet, who was the driving force behind La Joux Perret brands Arnold & Son and Angelus who takes up the reins as head of innovation and marketing at Sellita. He was quickly joined by Johannes Jahnke, the Christopher Ward watchmaker who developed the brand’s in-house SH21 movement, as director of development.

Sellita isn’t yet revealing how many new movements it will be developing but aims to have the first ready in 2019. “We’ll start with one movement and grow step-by-step,” says Chaulmontet. “We don’t need hundreds of calibres; a basic watch brand will only need two to three automatics”.

As part of the move Miguel Garcia, Sellita’s CEO and owner, admits that the previously secretive business needs to better communicate its role within the industry and after several months Chaulmontet eventually agreed to our request to visit the facilities.

Sellita was founded in 1950 as an assembly house, buying ébauches (movements in kit form) from ETA, assembling them and reselling the completed movements to watch brands. Quite how this curious business model came to be is not entirely clear but, for a time, Sellita was ETA’s biggest single customer. Then in 1990, ETA finally began assembling the components it produced into finished movements; suddenly ETA and Sellita were competitors, but only one produced the raw components.

The landscape shifted most dramatically in 2002 when Nick Hayek Sr. announced ETA would stop supplying ébauches to companies outside of the Swatch Group beyond 2006. While this news deeply troubled the watch brands who had come to rely on kits from ETA, it was far worse for Sellita, which relied entirely on this supply line.

Sellita, together with neighbouring La Joux-Perret, complained to the Swiss competition authority which ruled that ETA would have to maintain the supply of ébauches until 2010. While the countdown had been extended, it was clear that Sellita would need to make major changes to survive.

So, in 2004 Sellita began producing its own movement, the SW200, cleverly based on ETA’s out-of-patent automatic workhorse the 2824-2, which was introduced in 1981. The identical form factor meant existing 2824-2 customers could now choose a Sellita movement instead of the ETA without having to alter their watches to accommodate.

Dr Chaulmontet, explained: “The price is everything. If you achieve it technically but it costs CHF300-400 you’re dead, nobody wants your movement. So, you have the technical issue, the price and the time pressure. I wasn’t here at the time but the industry thought they would never make it.”

But Sellita achieved what it set out to accomplish and continued releasing ETA ‘clones’. The SW300 and SW500 are based on ETA’s more recent automatic, the 2892, and the Valjoux 7750 chronograph respectively. The company’s only original movement currently on the books, the diminutive SW1000, was designed in 2014 as a high-end ladies automatic and for use within men’s tonneau-shaped cases.

Today the business is made up of 500 staff based at three locations at Chaux-de-Fonds and Jura in Switzerland and Glashütte in Germany. But the business is not a vertical manufacture, nor does it aim to be. That would require, at Sellita’s own estimation, five times as many employees to produce the 200-400 million individual components the business makes use of each year. Instead it prefers to remain part of Switzerland’s more traditional infrastructure of supplier and customer having developed its own network of 100 Swiss suppliers. However, where a component cannot be sourced to meet Sellita’s quality and price requirements, the firm takes a pragmatic approach and manufactures it.

To illustrate the point on the first step of our tour of Sellita’s Building 2 in Chaux-de-Fonds, Dr Chaulmontet shows us date rings being pad-printed and then automatically checked for quality by software and a magnified camera feed. In such cases Sellita now also designs and builds its own machinery – under the Sellita Engineering banner – and has done for four years; the factory floor is filled with telltale powder blue chassis, filled with custom-built automation.

However, the bulk of the mechanisation at Sellita is reserved for sub-assembly; tasks such as setting rubies into mainplates via thin, pressurised jewel-loaded tubes or inserting ball bearings in rotor assemblies and then testing that the load is spread out evenly over each of the bearings.

Quality control is also rigorously enforced as, for a volume business such as Sellita, reliability (along with unit price) is key. To this end numerous measurements are made of each component and stored, eventually being cross-referenced to the serial number of the finished movement it is used within. This system results in huge quantities of stored data but, should any problems occur, this level of traceability allows Sellita to quickly track down the root cause.

Sellita is also one of the few places producing sufficient volumes to justify a full-time laboratory, complete with £1.1m electron microscope and mass spectrometer. As well as checking the surface quality of components the lab, which opened two years ago, can assist the engineering effort by identifying substances which can be helpful in tracing the source of chemical reactions.

The lion’s share of workshop space is given over to Sellita’s hero product, the aforementioned SW200. Sellita produces around 500,000 of the movements each year and while the sub-assembly is heavily automated, much of the final assembly is performed by hand with batches of movements moving from bench to bench on a vintage set of manual Lanco rails, rather than the more modern system which automatically transfers single movements between benches.

Sellita supply movements to some 300 brands, but it would be inaccurate to suggest that the company’s sole output is finished movements. There are finished watches too.

For some watch brands it makes more financial sense not only to use one of Sellita’s movements but for Sellita to complete the final assembly too. The brands in question ship the required cases, crowns, dials, pushers, hands and straps to Sellita, which then builds the completed watch around its own movements.

There are fully assembled watches from a number of different brands, sat in fully branded trays while one brand even has its own dedicated department within Sellita, which focuses solely on assembling its watches. The brands in question are a mixture of privately owned and group affiliated - and include big names from the major groups - however QP agreed to respect Sellita’s confidentiality agreements as a condition of entry.

Everyone knows that this happens within the industry, but that doesn’t alter how unsettling it is to see it for the first time. While these watches aren’t from brands claiming to be manufactures – this is not third party passed off as in-house or Chinese passed off as Swiss – it should give you cause to wonder which factory your watch actually comes from, if that matters to you.

With Sellita’s new acquisitions, both human and mechanical, the company could drastically widen its horizons. After all, Chaulmontet was better known for tourbillons and complicated chronographs during his time at Arnold & Son and Angelus.

“We have the ideas and we have the people,” he confirms. “We could do any movement we want but there’s no market for a triple axis tourbillon, we would never sell 100,000 pieces of it. It’s not our business, we’re organised to make high quality at high volumes. The reality is the client is king and we produce movements they want to buy, not the other way around. We start and end the discussion with the price.”

Sellita’s continuing investment, at a time when brands are actively seeking out alternatives to ETA movements, has made the firm the main contender for the business that ETA has pledged to ignore.

“We have a stronger and stronger position for the future,” agrees Garcia. “And our customers will support us after 2020. I hope. For them it is really important that Sellita continues to exist. We don’t have the arrogance nor the wish to completely replace ETA, but we have a responsibility to be ready if they stop delivering.”

The pertinent word there being ‘if’, meaning the move is not without risk. Should ETA reverse its decision to end supply, then Sellita could be left in a calamitous position.

“It could close the company,” Garcia adds dramatically. “The market will not need Sellita anymore, I don’t think. [But] we existed before ETA stopped supplying kits. Why did we supply one million movements a year? Not because I have beautiful blue eyes, but because we are a dynamic company, we serve our customers and they are happy to work with us.”

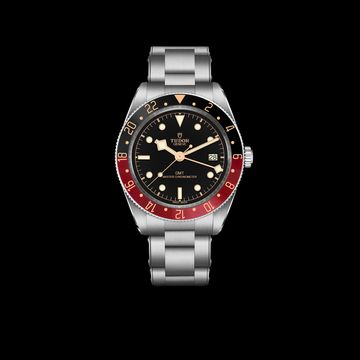

All watches shown in this story used Sellita calibres in one form or another.