We talk a lot about chronographs, as watch lovers. So much so, in fact, that in 2015 we dedicated an entire issue of QP to the complication, and at SalonQP we hosted an exhibition dedicated to the history and development of the chronograph, from Louis Moinet to Audemars Piguet's Michael Schumacher Laptimer.

There are reason for this: chronographs are functional, steeped in history and (usually) good-looking. Some of the most lusted-after watches of all time are chronographs, and their mystique drives collectors to new heights of obsession on a daily basis. Check out, if you haven't already, our list of little-known facts about the Rolex Daytona.

Chronographs are also terrifically difficult to make; until relatively recently, very few manufactures had an in-house chronograph calibre to their name - which is why we get so excited when a top-end one breaks cover or when we get a few of them together in the same room and let one of watchmaking's great minds, Kari Voutilainen, give his verdict on each.

But what are the hallmarks of quality when it comes to chronograph manufacture? Above all, we prize smoothness, solidity and reliability: does the second hand twitch when you re-set, or take a momentary pause before it sets off? If it's a flyback, does it instantly begin moving again from zero when you fly it back? How hard do you have to push the pushers, and is there a discernible heavy clunk when you do so? Does it perform smoothly, time after time?

Chronograph brands address these concerns with much talk of "vertical clutches" and "column wheels". But what are these components bringing to the table - and what are the alternatives? Here to lay all plain before you is watchmaker Peter Roberts, constructor of the five-handed chronograph, and former watchmaking teacher at Hackney Technical College, where he taught the likes of Peter Speake-Marin and Stephen Forsey.

No brakes?

"The best way to understand why some chronographs feel different from others is to understand what’s actually happening when you press the pusher. On a standard two-button chronograph, when you press the top pusher to start things off, a lot of things happen."

First of all, it releases the brake – which has been preventing the central seconds hand from moving. Not all chronographs have a brake – cheaper ones might rely on a friction spring to keep the hand stable (although this is fairly uncommon now). The disadvantage here is that a big knock to your watch can jolt the hand out of place, because it’s not in gear with anything else, and can be relatively heavy, especially if it’s got a “lollipop” style weight on the end. And if there isn’t enough tension in the friction spring, the second hand will wobble slightly when you start the mechanism thanks to a slight backlash from the wheels."

Hammer time

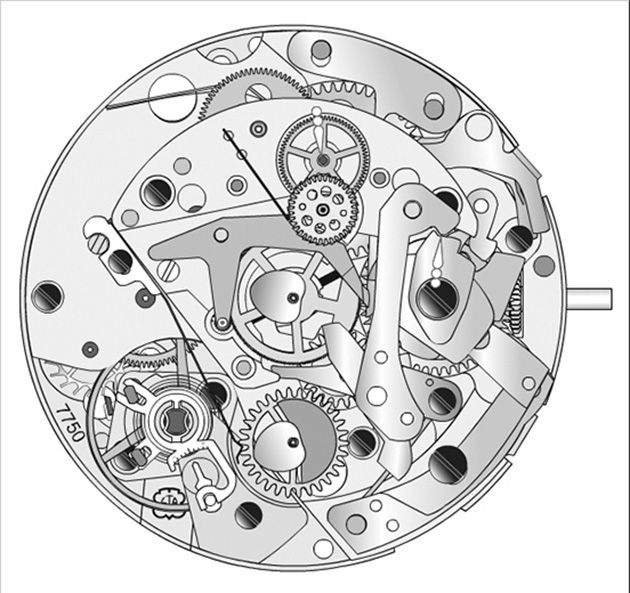

"Once the brake is off, most chronographs then cock, or reset, the hammers – like cocking a rifle. In a movement like the Valjoux 7750, with a lever cam, they are usually set against a heart-shaped cam, which keeps the hands at zero. The hammers are what make the hands snap back to zero when you re-set the chronograph; in doing this now, the watch is preparing for when you press the second pusher.

Moving the hammers is the main reason starting a chronograph can feel heavy; there’s a lot of work in cocking them back. You may find that if you start, stop and start again, the second time you press start it’s not as heavy – because the hammers are already back."

"If you have a column-wheel, like the Valjoux 72 does, the hammers are kept away from the cams, so the first push doesn’t need the energy to cock them. A Daytona with one of these movements will be nice and silky, and doesn’t vary at all."

Let the clutch out

"The third thing that happens is the chronograph mechanism engages with the geartrain of the watch. This happens either via a rocking pinion, a lateral clutch or a vertical clutch. A rocking pinion – as used on the Valjoux 7750 – is the most economical, the cheapest to make. A lateral clutch (or coupling clutch) meshes the gears together – a stationary gear joins a moving one. It’s the most elegant to look at, from a watchmaker’s point of view. At the same time, the action of the lever cam, or column wheel, has started the minute and hour counters running."

A vertical clutch means the gears are always engaged and works more like the clutch plate in a car. It’s technically superior, most of all because it eliminates the small sidestep of the second hand that you sometimes get with a lateral clutch. But you have to ask: how much of an advantage is that to you? It’s worth about 1/10th of a second, which is about as accurate as you can be with a chronograph in any case. And a vertical clutch isn’t much to look at; there’s nothing for the connoisseur. The Valjoux 72 is a very nice movement to look at."

"Vertical clutches aren’t a new idea – they first came out in the 1940s. They became flavour of the month again about ten years ago, when people started going back to them.

Lever or column?

"Either a lever cam or a column wheel controls the stop-start-reset of the watch. One benefit of the latter is that the hammers don’t need cocking, so the first push will be silky-smooth and consistent. People often equate column wheels with a lack of hand-shaking; that’s actually all down to the clutch. The reason is that you almost never get a column wheel chronograph with a lateral clutch – they’re usually vertical – so the wrong part is being thanked for the improvement."

"Column wheel works like ROM [Read-Only-Memory] in a computer. It rotates a set distance when you press the pusher, and the lever cam does the same thing in a more simplistic way. Generally speaking, the lever cam is more clunky. It’s a set of cleverly designed handles on the mechanism with a 'wig wag' effect. It’s much less expensive to make than a column wheel, as the parts can just be stamped out. A column wheel is more precise to make, and takes more levers and springs to get it working."

Stop: Reset

"When you stop the chronograph, you disengage the drivetrain from the chronograph mechanism, using the clutch again, and you apply the brake – or friction spring. That’s pretty straightforward. The hammers don’t go anywhere at this point."

When you reset the chronograph; which you can only press when the chronograph has stopped, because there’s a block which prevents it being activated (unless it’s a flyback mechanism), you disengage the brake, the hammers hit the cams and return all the hands to zero. A flyback performs the same function, but it then immediately activates the clutch again to begin the whole process. Hence a flyback can also feel heavy if it has to re-cock the hammers."

Pause for thought?

"As an interesting side point: some flyback chronographs are able to resume timing with almost no pause; others seem to pause before timing resumes. It sort of misses the point of a flyback to use this as a measure of quality, though: most people don’t realise this, but originally a flyback was intended for pilots to synchronise their watches to a precise signal – say, over the radio. They would press the flyback, hold it for a second or two, and let go at the exact point. Then you can compare the timing of the running seconds with the chronograph seconds, and find out whether your watch is fast or slow – important information for a navigator. People tend to want to use it like a split seconds, but that’s not the point."